Home » Publications

Category Archives: Publications

• Article: The effects on insects of plant-associated microorganisms

We are delighted that the last two chapters of Élisée’s thesis have just been jointly published in the journal Microorganisms. He only just completed his PhD! They discuss the effects of beneficial microorganisms associated with soybean roots on the health of insect populations of the second and third trophic levels (an herbivore and its natural enemies).

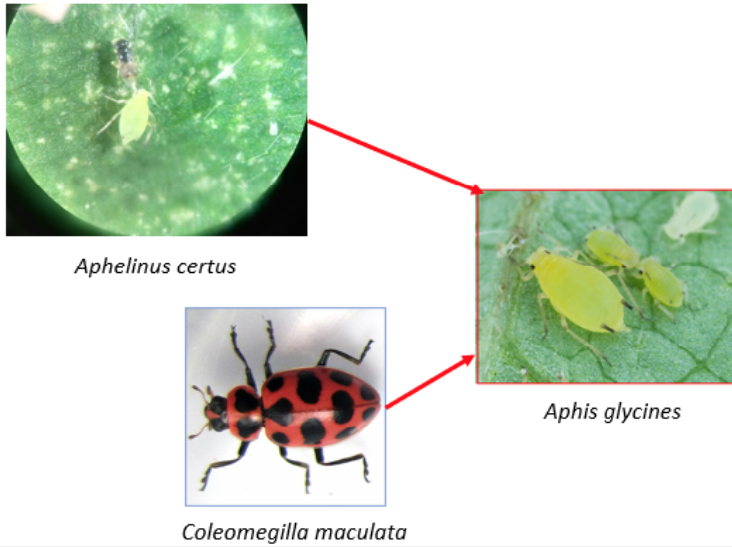

Beneficial microorganisms such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobium bacteria are known to modify plant performance traits through the supply of important nutrients, especially phosphorus and nitrogen. Previous studies looked at these interactions yielding variable results depending on the context. We examined at the cascading effects that beneficial organisms can cause on insects of the second and third trophic levels. We first wanted to confirm, in a controlled environment, the influence on the soybean aphid (Aphis glycines, second trophic level) of the tripartite symbiosis between an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (Rhizophagus irregularis), a bacterium (Bradyrhizobium japonicum), and the soybean plant (Glycine max) (First article). This study showed a significant increase in aphid colony growth in the presence of the double inoculant, mycorrhiza plus rhizobium and, albeit less so, in the presence of the rhizobium inoculant alone. This effect on the aphid is certainly a consequence of changes in plant chemistry induced by the microorganisms. The study shows that two symbionts can improve the performance of plants and phytophagous insects beyond what each symbiont can provide alone.

Secondly, we were interested in the effects of these same inoculants on the natural enemies of the soybean aphid, the predatory lady beetle (Coleomegilla maculata) and the parasitoid (Aphelinus certus) (Second article). The only significant result was with the parasitoid that showed a significant decrease in the rate of emergence from the pupal stage in the presence of the rhizobium inoculant. No difference was observed for any other fitness variable measured in either natural enemy.

In the light of the results of these consecutive studies, it appears that the confirmed advantages that microbe-plant symbioses confer upon the second trophic level are little transferred to the third.

- Dabré ÉE, Hijri M, Favret C. 2022. Influence on soybean aphid by the tripartite interaction between soybean, a rhizobium bacterium, and an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Microorganisms, 10(6): 1196. DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms10061196

- Dabré ÉE, Brodeur J, Hijri M, Favret C. 2022. The effects of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and rhizobium symbioses on soybean aphid mostly fail to propagate to the third trophic level. Microorganisms, 10(6): 1158. DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms10061158

• Article: Insects and mycorrhizae in soybean fields

We have published a new article in the journal PLOS ONE. This publication is the first one based on the research of doctoral student Élisée Emmanuel DABRÉ.

The use of beneficial microorganisms, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as biofertilizers in agricultural systems, has gained particular interest in recent years due to their positive effects on plant growth and crop yield. While many studies have focused on the indirect effects of these inoculants on insects associated with plants in controlled and semi-controlled environments, very few field investigations have been done.

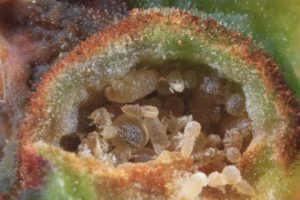

We carried out an inventory of phytophagous insects and their natural enemies in soybean fields inoculated with spores of the mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis, the rhizobial bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and a bacteria promoting plant growth, Bacillus pumilus.

We showed in this study that inoculants reduced the abundance of soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) only in the presence of potassium. We also noted a decrease in the number of leafhoppers in the presence of potassium alone, indicating its probable role in the nutrition of these insects. Finally, we detected a negative correlation between the rate of mycorrhizal colonization of the roots and the abundance of piercing-sucking insects. Given that such insects are major vectors of plant disease, it seems that increased mycorrhizal fungal colonization can help protect crop plants.

• Article: The Odonata of Quebec

The Ouellet-Robert Collection has a wonderful set of dragonfly and damselfly specimens (insect order Odonata) thanks in large part to the efforts of its eponymous founder, Adrien Robert. Indeed, the Odonata collection is so good that we chose a damselfly, the superb jewelwing (Calopteryx amata), as the emblem for the collection.

Before I arrived at the University of Montreal, seed funding for Canadensys from the Canada Foundation for Innovation had paid for the digitization of the specimen data associated with the collection’s Odonata. As a first tentative to better integrate the activities of the various insect collections in Quebec, and possibly to federate a more ambitious collaboration, with funding from the Quebec Centre for Biodiversity Science, colleagues and I visited six other Quebec collections and added their Odonata specimen data to the mix. The result is an impressive dataset including 37,000 occurrence records, from 616 different locations, for 137 species. This dataset, whose description is published in the Biodiversity Data Journal, is free to download and use for species distribution modeling, analyzing changes across time, and any number of other research topics. Given that many Odonata species in Quebec are at the northern limits of their geographic range, their possible range expansions northward may be good indicators for measuring the effects of climate change.

This publication represents the second one in less than a year focusing on the activities in the Ouellet-Robert Collection. The first was an overview of three computerization initiatives, including the Odonata specimen digitization, whereas this second one focuses on the Odonata data themselves.

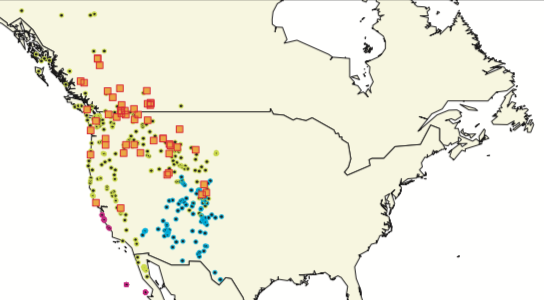

• Article: Aphid climate niche

The dominant paradigm is that the host plant distributions determine those of plant-feeding insects. However, climate is known to affect the distribution of other organisms, including plants, so who’s to say it doesn’t affect plant-feeding insects too? A group of colleagues sought to answer that very question. We geographically modeled climate variables and host plant and aphid distributions to measure the amount of overlap and how much one may affect the other. For example, perhaps it’s climate conditions that preclude the aphid from being co-located with its host in particular locations. To our North American dataset we added the Cinara aphid collection localities from French and Chinese colleagues, and we used publicly available climate and conifer tree distribution data.

In our paper in Ecology and Evolution, we showed that the distributions of most Cinara species overlap completely with those of their hosts. In those cases, we could not say that climate played a direct constraining role in the aphids’ distributions, but only insofar as it affected that of the host plants. However, almost a third of the Cinara species were present in a reduced portion of their hosts’ range. This result suggests that aphid geographic distribution is constrained by both host and climate factors, and not by host alone.

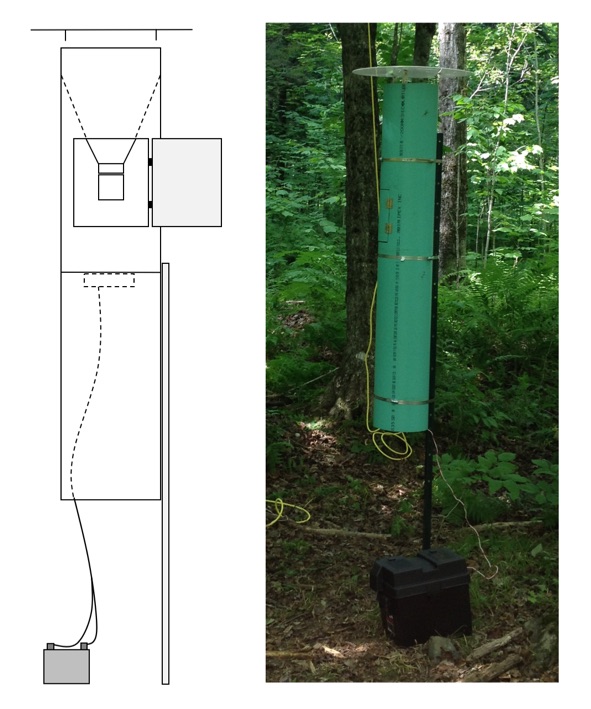

• Article: Voegtlin trap

During my M.S. research, my advisor David Voegtlin gave me a set of medium-sized suction traps that he had developed and built for catching aphids. As I sorted hundreds of aphids, I was amazed at the diversity of other insects in the traps and vowed that I would one day take a closer look at it. One of the first things I did when I arrived at the University of Montreal, was to build my own set of “Voegtlin traps” and set them up along a 150 m transect in the forest of the University’s Laurentian Biological Research Laboratory. We sampled several summer weeks, with suction traps and small Malaise traps set up side by side to compare the efficacy of these two trapping methods.

Over the course of several subsequent years, a small army of undergraduate students sorted the insects in a single week’s worth of that material. One of them, Alexis Trépanier, spent two full semesters classifying the Hymenoptera into “Operational Taxonomic Units”, ending up with just shy of 200 OTUs! He, undergraduate Diptera-sorter Titouan Eon-Le Guern, master’s student computer analyst Vincent Lessard, PhD student Thomas Théry and I just published the results of this project in the journal Insect Conservation and Diversity.

Along with describing the Voegtlin suction trap in detail, we found that these traps were excellent at capturing tiny insects, especially small parasitoid wasps known as Microhymenoptera and the very diverse family Phoridae (true flies, Diptera). Not only are these traps great for species discovery generally, but we found that the ensemble of the insects that they caught was different for each trap along the transect, despite the fact that the traps were only 50 m apart. This suggests that there is a fair amount of insect community heterogeneity in the Laurentian forest.

This summer, we’ve placed three pairs of traps in similar habitat replicates. We’re hoping to find out if that community heterogeneity is more or less random throughout the forest, or if it is patchy, based perhaps on the surrounding vegetation. With any luck, there’ll be a follow-up post in a couple years.

• Article: Digitizing the collection

During the past few years, the Ouellet-Robert Entomological Collection personnel have been working towards increasing the use and value of the Collection. Today, entomology researchers especially need electronic data. In a recent publication, we described three computerization initiatives.

First, we examined each drawer of pinned specimens and each vial rack of alcohol-preserved specimens, and we graded the conservation health of these units across eight criteria (for example, the condition of the specimens, or their labels, or their storage containers). With these data, for internal use only, we are better able to target certain parts of the collection with the greatest need.

Secondly, we created a list of the species in the Collection, the number of individuals of each species, and if at least one specimen was had been collected in Quebec or North America. These data, made available on line, are intended for researchers who want to know what material is the Collection so that they can pay us a visit or ask for a loan or more information. We counted 1.5 million specimens, of which a third are pinned, and 20,000 species, of which half are from Quebec.

Finally, we digitized the specimen label data of certain aquatic insect groups, most importantly the dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata) of which we have a lot of material thanks to the effort of our previous curators, Jean-Guy Pilon and Pierre-Paul Harper, but especially Adrien Robert. These data will be useful for, among others, estimating the geographic distribution of Odonata over time and evaluating the effects of environmental change. In fact, we have already added to this dataset by computerizing the specimen label data of other Quebec insect collections: an article describing the combined dataset is in preparation.

The combination of these three new data resources represent but a starting point for a new digital age in the Ouellet-Robert Collection.

• Article: A North American aphid invades new territory

Aphis lugentis is an aphid species relatively common in North America, feeding primarily on Senecio, a genus of the daisy family. This aphid species had recently been found in southern France and in a new publication, we document its presence across the Mediterranean in Tunisia, as well as in South America, namely Argentina, Chile, and Peru. In order to confirm the identity of our samples, we examined them under the microscope and sequenced their barcode gene. Publication of the note in the Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington implicated eight co-authors from four countries, including two undergraduate interns in the Favret Lab.

Ortego J, Ayadi M, Ben Halima Kamel M, Juteau V, Marullo-Masson D, Nieto Nafría JM, Bel Khadi MS, Favret C. 2019. The spread of the North American Aphis lugentis Williams (Hemiptera: Aphididae) to Africa and South America. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 121(1): 128-134. DOI: 10.4289/0013-8797.121.1.128

• Article: The Cannabis aphid in North America

The recreational use of marijuana becomes legal across Canada today. Of course increased cultivation of Cannabis sativa will accelerate research on this species, as was highlighted in the scientific journal Nature. It will also mean the need to protect the crop against insects and other injurious organisms. One such insect is the Cannabis aphid, Phorodon cannabis. This Eurasian species was recently introduced to North America. In a recent publication, my colleagues and I brought attention to the presence of this insect in the United States and Canada, in fields and greenhouses. We also discussed its biology and taxonomy. The aphid has already caused crop damage but its full economic impact remains to be seen.

Cranshaw WS, Halbert SE, Favret C, Britt KE, Miller GL. 2018. Phorodon cannabis Passerini (Hemiptera: Aphididae), a newly recognized pest in North America found on industrial hemp. Insecta Mundi, 662: 1-12. URL: http://journals.fcla.edu/mundi/article/view/107029

• Article: Revision of the mealy plum aphids

The mealy plum aphid, Hyalopterus pruni, along with two other species of Hyalopterus, are important pests of peaches, apricots, plums, and almonds. Unfortunately, there were 13 separate species names for only three valid species. In order to associate the 13 names with the three species, we published a taxonomic revision of the aphid genus Hyalopterus. The project involved five authors from five different countries, and the results were published at the end of 2017. Establishing the correct names for the three valid species will help researchers on these pest aphids better communicate their work. The paper is available at the Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. Or just drop Colin an e-mail for a personal delivery!

Favret C, Meshram NM, Miller GL, Nieto Nafría JM, Stekolshchikov AV. 2017. The mealy plum aphid and its congeners: A synonymic revision of the Prunus-infesting aphid genus Hyalopterus (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 119(4): 565-574. DOI: 10.4289/0013-8797.119.4.565

• Article: Protecting the name Adelgidae

Adelgids are sometime conifer insect pests; of particular note is the hemlock woolly adelgid. A large number of species alternate host, forming galls on a spruce one year and migrating to the bark or needles of another kind of conifer the next (fir, hemlock, larch, pine). While preparing a catalog of adelgid species, I discovered that there are actually three names referring to the same family. According to the rules of the zoological nomenclature, when two scientific names apply to the same animal (synonyms), it is the older that takes precedence. Unfortunately, the other two names, published in 1901 and early 1909, both have priority over Adelgidae, published in late 1909. Because Adelgidae is used much more often than the other names, to protect the stability of the nomenclature and the research on this important insect family, I prepared a petition, submitted to the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature, to protect the name Adelgidae by suppressing the other two. With the support of many of my fellow aphidologists, I am confident that my request will be granted, but in case it is not, we will have to start using the name Chermaphididae to refer to this family!

Favret C. 2017. Case 3714 – Adelgidae Schouteden, 1909 (Insecta, Hemiptera, Aphidomorpha): proposed conservation by reversal of precedence with Pineini Nüsslin, 1909 and Chermaphidinae Hunter, 1901. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 74(2): 55-59. DOI: 10.21805/bzn.v74.a019